Einstein's general relativity (GR) is a beautiful theory which explains how mass and energy interact with space-time, creating a phenomenon commonly known as gravity. GR has been tested and retested in various physical situations and over many different scales, and, postulating that the speed of light is constant, it always turned out to outstandingly predict the experimental results.

Nevertheless, physicists suspect that GR is not the most fundamental theory, and that there might exist an underlying quantum mechanical description of gravity, referred to as quantum gravity (QG). Some QG theories consider that the speed of light might be energy dependent. This hypothetical phenomenon is called Lorentz invariance violation (LIV). Its effects are thought to be too tiny to be measured, unless they are accumulated over a very long time.

Gamma-ray burst as benchmark

So how to achieve that? One solution is using signals from astronomical sources of gamma rays. Gamma-ray bursts (GRBs) are powerful and far away cosmic explosions, which emit highly variable, extremely energetic signals. They are thus excellent laboratories for experimental tests of QG. The higher energy photons are expected to be more influenced by the QG effects, and there should be plenty of those; these travel billions of years before reaching Earth, which enhances the effect.

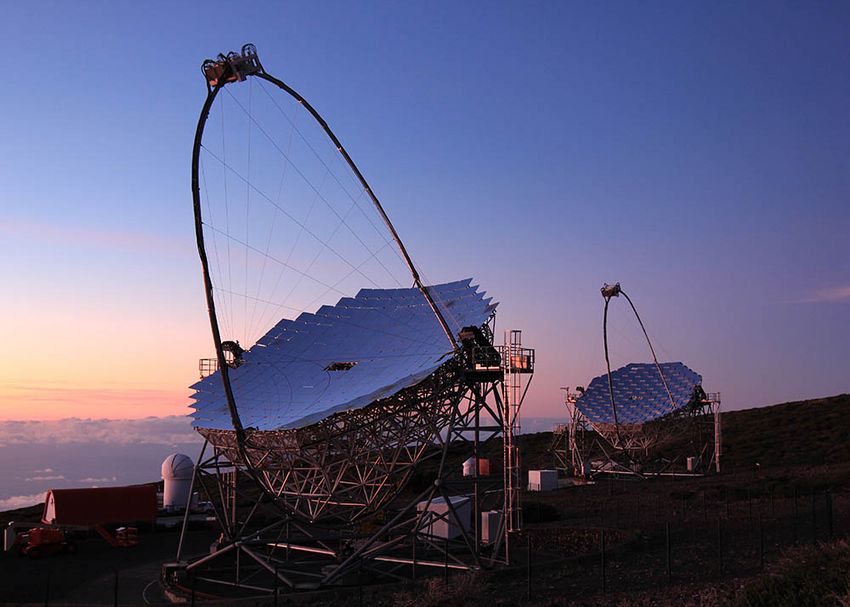

GRBs are detected on a daily basis with satellite borne detectors, which observe large portions of the sky, but at lower energies than the ground-based telescopes like MAGIC. On January 14, 2019, the MAGIC telescope system detected the first GRB in the domain of teraelectronvolt energies (TeV, 1000 billion times more energetic than the visible light), hence recording by far the most energetic photons ever observed from such an object. Multiple analyses were performed to study the nature of this object and the very high energy radiation.

Foothold for future test on quantum gravity

A careful analysis then revealed no energy-dependent time delay in arrival times of gamma rays. Einstein still seems to hold the line. “This however does not mean that the MAGIC team was left empty handed”, said Giacomo D’Amico, a researcher at Max Planck Institute for Physics in Munich; “we were able to set strong constraints on the QG energy scale”. The limits set in this study are comparable to the best available limits obtained using GRB observations with satellite detectors or using ground-based observations of active galactic nuclei.

In contrast to previous works, this was the first such test ever performed on a GRB signal at TeV energies. With this seminal study, the MAGIC team thus set a foothold for future research and even more stringent tests of Einstein’s theory in the 21st century. Oscar Blanch, spokesperson of the MAGIC collaboration, concluded: "This time, we observed a relatively nearby GRB. We hope to soon catch brighter and more distant events, which would enable even more sensitive tests."